For the first time in many years, I was organised enough to actually do something about York’s Resident’s Weekend this year. The overall jist is that for one weekend a year, the people who live in York (identified by having a York Card bit on their library cards) get to play tourist on the cheap as a thank you for putting up with the 7 million people who visit the city each year.

The main event for me was joining some friends on a tour of York’s very own nuclear bunker, which is normally tricky to visit because it’s only open twice a month if you’re not a group. Our tour was conducted by one of English Heritage’s knowledgable guides and there was a huge amount of information to try to take in.

Until 1991, it served as the Yorkshire Regional Headquarters for the Royal Observer Corps, which I hadn’t really heard much about since their role in the Second World War.

This organisation was made up almost entirely of a rotation of volunteers, each of which had to spend two hours a week practicing and training, with occasional 12, 24 or 36 hour stints once a year. It’s role was redefined in the late-1950s to be a network of relatively low-tech observation stations that would monitor and track nuclear strikes.

The observers had three tools available to help with their task. Ionising radiation was monitored from inside the bunkers with a sort of periscope with a geiger counter stuffed up it. Any blasts or bombs going off were watched using a pinhole camera, which had four pieces of paper inside a metal box with four small holes drilled in it. A hypothetical nuclear blast would burn a circle into the paper, through the hole. The paper was marked with a calibrated sequence of lines to give direction and elevation. But mostly volunteers were expected to rely upon a standard issue pair of mark 1 eyeballs.

The bunkers were spread evenly across the entire country, which was quite an investment when they were built in the 1960s, but their equipment and processes received almost no upgrades since then. If you ever see a green metal trapdoor in a field, chances are that it leads down a ladder into a 20′ tin box. Within which there would be three volunteers with sufficient supplies to last 30 days underground. This doesn’t seem like my idea of fun, but then neither does Nuclear War.

Since they were stood down, ownership of almost all of the bunkers reverted to the landowner. Some have been put up for sale on eBay, others were dug out and demolished but most of them were ignored and left to deteriorate. If keeping track of them seems like fun to you, then the Subterranea Britannica would love to hear from you. They’ve visited all of them and mapped them out so that you can go exploring too. But try not to get caught trespassing when looking for your nearest one.

I think there were about 300 volunteers for the York HQ. If the warning went up, then everybody had to drop everything and leg it for the bunker. The first 60 people who got there were allowed in, then the blast doors were shut. There is enough living space in the canteen and bunks for 20 people, so it was a constant rotation between sleeping, living and being on duty. In addition to the volunteers, there was an RAF commandant, two mechanical engineers to look after the generator, water and air supplies, two BT engineers to look after the telephone exchange and three Home Office scientists who combined observations with Met Office data to predict where the fallout was going and who warned adjacent sectors and countries.

The larger of the two dorms. You can see the site's luggage storage shelf in the top left. Marked as the women's dorm, but I can't imagine people would have been that bothered about such distinctions if there were bombs going off.

Each volunteer was allowed the equivalent of a carry on bag to last them for the 30 days. There were no shower or bath facilities because there was nothing like enough of a water supply, so I shudder to imagine what it was like on day 29 with 60 people rushing around inside a sealed box who’s air supply was only refreshed every now and again to maximise the life of the external air filters.

Originally, it was fitted with a patch cable style of exchange, but it was upgraded to a modern automatic exchange in the late 1970’s. Amusingly, it’s fitted with a Mitel SX2000, which I have a certain amount of professional experience with..

I appreciated the brutal simplicity of the generator room’s automatic firesuppressant system. If the room got too hot, then a single strand of lead solder melted through, which dropped the blast door over the only exit and then flooded the room with CO2, which smothered the diesel generator, the fire and anybody unfortunate enough to be in the room when it went off.

The one nod to upgrading the technology was in the early 1980s when there were a small handful of Met Office automatic detectors issued for trials. These were originally designed to monitor direction and intensity of thunderstorms, but with the addition of a top secret module that had to be removed before the public were allowed anywhere near it, they also did the job for nuclear blasts. Unfortunately, they also still detected thunderstorms, so caused any amount of excitement.

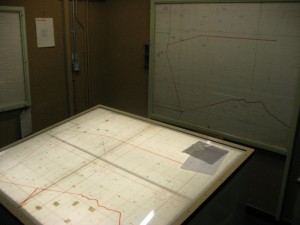

The main operations room was straightforward. If they were on alert, then a number of telephone and radio operators contacted each of that regions stations every four minutes to ask for updated observations. If one of them had noticed a bomb going off, then the operator would take down the numbers and shout out “TOCSIN BANG”. These would then be triangulated with other observations from the network on the local maps which gave the approximate area of impact, that was logged on a large piece of wood and passed onto the regional maps, whereupon the triangulators reset and waited for the next bomb to land.

Nowadays, the ROC is a social organisation. You can read more about their history on their website http://www.rocassoc.org.uk/open/national/roca/hist_ng2.htm.

There aren’t many left, but the bigger sector bunkers included the necessary infrastructure to maintain regional government, until national government could be re-established. This included facilities like a BBC studio and transmission equipment that could play back the public information recordings. In the end, almost none of those recordings were transmitted. It was felt that asking the population to be prepared would have caused too much panic and uncertainty. One piece of trivia that amused me, apparently John Craven did most of the recordings in the 1970s.

How better to finish off a trip like this but with a pint and a lunch at the ever good Brigantes and a Punch and Judy show, courtesy of the city council.